About Syriac

Origins of Syriac

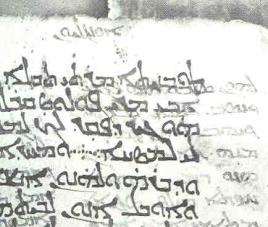

Syriac is a dialect of Aramaic, a language originally spoken by the Arameans in the 11th century BCE. By the 6th century BCE, Aramaic had become the lingua franca of the Near East, and it was used by groups such as the Chaldeans, Assyro-Babylonians, Persian Achaemenians, and Jews at the time of Christ. Syriac was the dialect of Edessa (present-day Urfa in southeast Turkey), and it became an important literary language around the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE. The earliest dated Syriac inscription is from 6 CE, and the earliest parchment, a deed of sale, is from 243. In November 411, the earliest dated manuscript was produced, and it is probably the first of its kind in any language.

By the 5th century CE, the oldest Syriac script, Estrangelo (“rounded”), was fully developed; West Syriac (Serto) and East Syriac were derived from it. (Beth Mardutho created the Unicode fonts for these Syriac scripts!) Two hundred years later, Semitic languages such as Hebrew and Arabic adopted the Syriac vocalization system and, in the 12th century, it was used by the Mongols in the formation of their own script. The spread of Syriac was mainly due to two factors: the growth of Christianity in the Semitic-speaking world and commerce on the Silk Road. A testimony of this rather remarkable expansion is the bilingual Chinese and Syriac text from Sian (Xi’an) in China. Today, a few million Indian Christians also follow the Syriac tradition. Within a few centuries from its origin, Syriac produced a wealth of literature in numerous fields – philosophy, religion, science, history, and linguistics.

Early Literature (1st—4th Centuries)

Early Syriac literature was produced in Mesopotamia, especially in and around Edessa, by pagans, agnostics, Jews, and Christians. Over sixty inscriptions – mostly pagan – and a few pieces of papyrus from the first three centuries still remain, but the texts are anonymous and cannot have their date or origin established. Their script is a mixture of Official Aramaic and literary Syriac. They represent the early development of the Syriac language.

Early Syriac literature was produced in Mesopotamia, especially in and around Edessa, by pagans, agnostics, Jews, and Christians. Over sixty inscriptions – mostly pagan – and a few pieces of papyrus from the first three centuries still remain, but the texts are anonymous and cannot have their date or origin established. Their script is a mixture of Official Aramaic and literary Syriac. They represent the early development of the Syriac language.

By the year 200 CE, the books of the Hebrew Bible were translated from Hebrew, likely by Syriac-speaking Jews and early Jewish converts. The earliest form of the New Testament, the Diatessaron, appeared at the same time, followed by a full Greek translation. Other works that were produced during the period were The Odes of Solomon, the story of the “Aramean Sage” Ahikar, and the Acts of Judas.

The fourth century witnessed the creation of the first major surviving texts. Of the writings of the “Persian Sage” Aphrahat, twenty-three Demonstrations remain, discussing topics of faith, love, prayer, war, humility, the Sabbath, and food. Another work of this period is the anonymous Book of Steps, dealing with spiritual direction.

Commentaries, expositions, refutations, letters, and poetry were produced on a large scale by Ephrem the Syrian, who was the most celebrated writer of the time. Although much of his fame resulted from falsely-attributed writings, Ephrem authentically produced a wealth of theological works in prose and artistic poetry and has been considered as “perhaps, the only theologian-poet to rank beside Dante.”

The Golden Age (5th—9th Centuries)

This period saw the greatest production of Syriac texts in disciplines including philosophy, logic, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, history, theology, linguistics, and literature. Some of the 70 most prominent authors are the poets Narsai and Jacob of Serugh, the Biblical commentators Ishodad of Merv and John of Dara, the scientists Sergius of Resh Aina, Severus Sebokht, and George of the Arabs, and the linguists Jacob of Edessa, Anton of Takrit, and Isho Bar Nun.

This period saw the greatest production of Syriac texts in disciplines including philosophy, logic, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, alchemy, history, theology, linguistics, and literature. Some of the 70 most prominent authors are the poets Narsai and Jacob of Serugh, the Biblical commentators Ishodad of Merv and John of Dara, the scientists Sergius of Resh Aina, Severus Sebokht, and George of the Arabs, and the linguists Jacob of Edessa, Anton of Takrit, and Isho Bar Nun.

The fifth century also witnessed the division of the Christian Church into many factions, and the Syriac tradition encompasses the rich diversity of all contrasting theological positions. Numerous theological debates arose during the time, bringing about the creation of many writings on the topic. The apologists Philoxenos of Mabbug and Babi the Great and theologians Dadisho, Isaac of Nineveh, Timothy I, Moshe Bar Kepha, and Theodore Bar Koni all addressed the Christological controversies resulting from the split.

Much of this theological and scholarly activity was centered in schools and monasteries such as the School of Edessa, School of Nisibin, St. Gabriel’s Monastery, and St. Moses the Ethiopian, the latter two of which are still in use today.

Through the Syriac Renaissance (9th —14th Centuries)

In the 4th century, Greek philosophy, logic, and science began to be translated into Syriac. In the 8th and 9th centuries, when the Arabic-speaking scholars and caliphs enlisted Syriac scholars to translate Greek sciences into Arabic, the scholars often translated the works into their native language first. Scientific works from other cultures, such as Persia and India, passed into Arabic via Syriac as well and, as a result, much of Arabic scientific terminology is rooted in Syriac. A noted example is the name of the chemical element Zirconium, which comes from Syriac “zargono” and means “color of gold.”

In the 4th century, Greek philosophy, logic, and science began to be translated into Syriac. In the 8th and 9th centuries, when the Arabic-speaking scholars and caliphs enlisted Syriac scholars to translate Greek sciences into Arabic, the scholars often translated the works into their native language first. Scientific works from other cultures, such as Persia and India, passed into Arabic via Syriac as well and, as a result, much of Arabic scientific terminology is rooted in Syriac. A noted example is the name of the chemical element Zirconium, which comes from Syriac “zargono” and means “color of gold.”

The most celebrated translator of this period was Hunayn Ibn Ishaq, who revised earlier translations and educated others in his trade. Another is Thabit Ibn Qurra – the author of scientific works in Syriac and Arabic and the translator of writings of Archimedes, Euclid, and Ptolemy. Thabit is also credited with introducing the mathematical theory of “amicable numbers.”

Along with this translation movement, native Syriac authors continued to flourish. In this period, Elijah of Anbar produced an extensive gnomic work, and his namesake Elijah of Nisibin wrote a chronography and Arabic-Syriac glossary. Bar Salibi produced many encyclopedic works on various topics, and Michael the Great composed a world history.

The 11th—13th centuries is sometimes called “the Syriac Renaissance.” One of the greatest writers of this time was Bar Ebroyo. A true polymath, he wrote over 20 books in theology, history, liturgy, medicine, philosophy, logic, mathematics, grammar, and poetry – even a book of jokes!

Decline of Syriac Literature (14th—19th Centuries)

Traditional historians mark the 13th century as the end of Syriac literature. However, while there was indeed a general decline in intellectual activity in the Middle East after the 13th century, Syriac writers continued to produce a considerable amount of works, most of which have not been studied or published. Writers of this period include Nuh the Lebanese, David the Phoenician, and Isaiah of Bet Sbirina, who produced a poetic account of the devastation of Timur Leng.

Traditional historians mark the 13th century as the end of Syriac literature. However, while there was indeed a general decline in intellectual activity in the Middle East after the 13th century, Syriac writers continued to produce a considerable amount of works, most of which have not been studied or published. Writers of this period include Nuh the Lebanese, David the Phoenician, and Isaiah of Bet Sbirina, who produced a poetic account of the devastation of Timur Leng.

In the 16th century, the Syriac mathematician Patriarch Ignatius Ni’matallah abdicated his office and was invited by Pope Gregory to join the Commission on Calendar Reform in Rome. Shortly after, he wrote an extensive criticism of the reform proposal which helped in shaping the Gregorian Calendar.

The 17th century witnessed the beginning of writings in the Neo-Aramaic vernacular dialect Alqosh, which became more popular in the 19th century under the influence of the American Missionary Press at Urmia. Another new phenomenon appeared at this time: the translation of western spiritual works into Syriac.

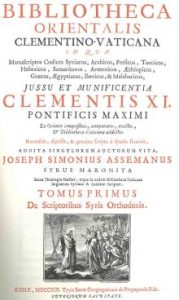

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the Maronite Assemani family produced a number of excellent scholars, most notably Joseph Simon Assemani. They played an important role in introducing Syriac heritage to the West. Joseph produced Bibliotheca Orientalis, the first and best encyclopedia of Syriac works and, along with his nephew Stephen, introduced the works of Ephrem the Syrian to Europe. The Maronite College in Italy continues this tradition.

In addition to the general decline in literary productivity in the Middle East during this period, Syriac-speaking communities faced persecution under Ottoman Turkish rule. The persecutions culminated in 1915 – called “The Year of the Sword” by the Syriac people – when hundreds of thousands were collectively massacred. This resulted in the migration of the Syriac people to other countries of the Middle East and the diaspora in the West.

The Modern Syriac Renaissance (20th Century)

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a revival of secular and religious Syriac literature. As a result of the end of World War I and the turbulent history that ensued, a spirit of ethnic identity that shaped modern literature swept across Syriac-speaking communities of the Middle East. Toma Audo, Chaldean Metropolitan of Urmia, composed a valuable large-size Syriac-Syriac dictionary. The Syriac Catholic Patriarch Afram Rahmani and his Orthodox counterpart Afram Barsoum were among the most distinguished Syriac scholars of the 20th century, each producing a large number of scholarly studies.

The late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed a revival of secular and religious Syriac literature. As a result of the end of World War I and the turbulent history that ensued, a spirit of ethnic identity that shaped modern literature swept across Syriac-speaking communities of the Middle East. Toma Audo, Chaldean Metropolitan of Urmia, composed a valuable large-size Syriac-Syriac dictionary. The Syriac Catholic Patriarch Afram Rahmani and his Orthodox counterpart Afram Barsoum were among the most distinguished Syriac scholars of the 20th century, each producing a large number of scholarly studies.

Journalism was a new genre of the century. Naoum Faiq founded the earliest Syriac periodical, Star of the East, in 1908, and the Neo-Aramaic periodical Kokhwa ‘Star’ appeared in Urmia. Today, a few dozen periodicals are published in those languages. A few translations from western books into Syriac also appeared, most notably Bernardin de Saint Pierre’s romantic novel Paul et Virginie (translated by Paulos Gabriel and Ghattas Maqdasi Elyas) and Racine’s play Athalie (translated by Abrohom Isu).

Additionally, most liturgical works were translated from Syriac into Malayalam, the language of the St. Thomas Christians. Among the most celebrated translators is Matta Konat. Along with the revival of Syriac literature, the 20th century witnessed an increased interest in the study of Syriac heritage by Western scholars. Today, there is an international conference on Syriac studies almost every year. Beth Mardutho sees itself as part of this Renaissance, bringing Syriac scholarship and Syriac-speaking communities together to preserve the Syriac heritage and its language.

Syriac Today

Today, Syriac is the liturgical language of a few Christian communities: The Syriac Orthodox Church, The Assyrian Church of the East, The Maronite Syriac Church, The Chaldean Catholic Church, The Syriac Catholic Church, and the various churches of the St. Thomas Christians in India. Syriac is also witnessing an expansion in Western universities. Since the late 1980s, the University of Oxford has offered a Master’s Degree in Syriac studies, and the University of Birmingham is following suit. Additionally, a Ph.D. in the language is obtainable at Mahatma Gandhi University in Kerala, India. In most major universities where it is taught, Syriac is classified in either the Semitic or religious studies departments.

Today, Syriac is the liturgical language of a few Christian communities: The Syriac Orthodox Church, The Assyrian Church of the East, The Maronite Syriac Church, The Chaldean Catholic Church, The Syriac Catholic Church, and the various churches of the St. Thomas Christians in India. Syriac is also witnessing an expansion in Western universities. Since the late 1980s, the University of Oxford has offered a Master’s Degree in Syriac studies, and the University of Birmingham is following suit. Additionally, a Ph.D. in the language is obtainable at Mahatma Gandhi University in Kerala, India. In most major universities where it is taught, Syriac is classified in either the Semitic or religious studies departments.

During the past few decades, four periodic international conferences dedicated to the Syriac tradition have emerged. The International Symposium Syriacum, North America-based Syriac Symposium, and conferences led by the St. Ephrem Ecumenical Research Institute and Lebanese Maronite institutions all convene every four years. At the community level, Syriac is being taught to children in a few private community schools in the Middle East, and magazines are being published in Syriac and Neo-Aramaic. A few publishing houses have emerged – in 2001, Beth Mardutho established the Beth Mardutho ePress.

As we enter the Third Millennium, we feel that there is a need for a center dedicated entirely to the study of Syriac heritage, one that will serve all Syriac communities in an ecumenical spirit. Beth Mardutho’s ultimate goal is to fulfill this need.